On Saturday 14 October, Australians voted in the 45th referendum to amend the constitution.

Only eight of 44 previous attempts had succeeded. In this case Australians were asked to say Yes to a three-part question: did we approve of a specific recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as the ‘First Peoples of Australia;’ to create a new body, to be called the Voice, which ‘may make representations’ to the federal parliament and government; and to grant parliament ‘power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the … Voice.’ The three parts would form an entire Chapter IX on their own.

Amending the Australian Constitution is exceptionally difficult, which is why only a handful have succeeded. It requires approval by a majority of voters nationally, and by a majority of voters in at least four of the six states. Of the 36 failed referenda, five had failed due to a 3-3 deadlock among the six states despite a majority voting for them nationally. The Voice referendum becomes the 37th failure.

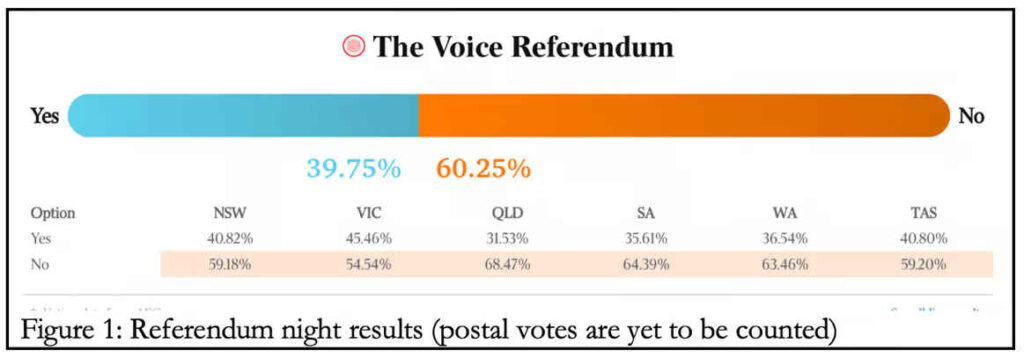

The results are shown in Figure 1. The proposal has been comprehensively defeated. The referendum went down 60-40 nationally and in every single state, with Victoria recording the narrowest 9-point margin.

Only 33 of the 151 parliamentary seats recorded a Yes vote. This included all three of Canberra, thus confirming that the Canberra bubble is a very real phenomenon. The Sydney seat of Barton, held by the Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney, voted No 56-44. Seats with high Indian-ancestry populations voted No, departing from support for Labor in the last election and indicating a reluctance to become third-class citizens behind Aboriginal and European-ancestry Australians.

The $365 million referendum, backed almost unanimously by the governing, educational, financial, media, and sporting institutions and funded generously by them using shareholder and public monies rather than their own, confirmed an alarming gap between the elites and the vast majority. It should but is unlikely to lead to any serious introspection by members of the elite.

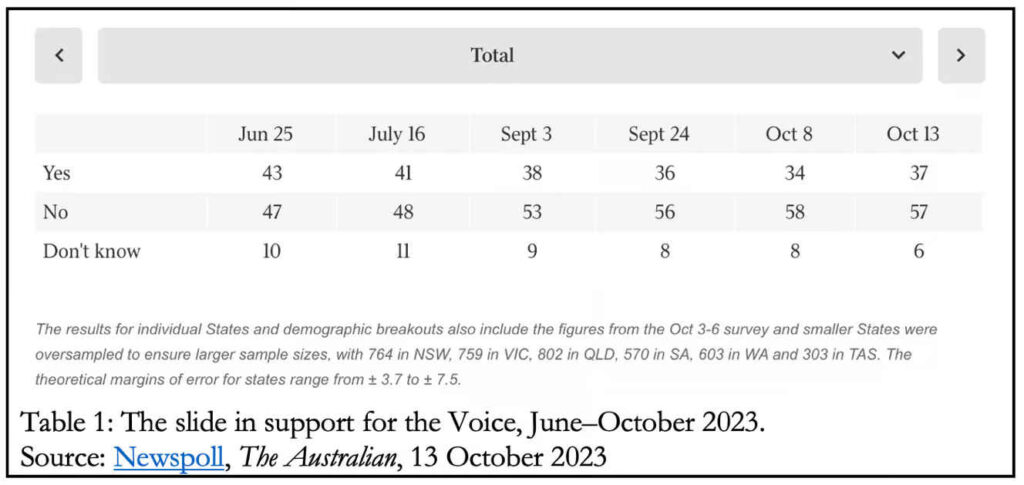

The downward slide in support for the Voice was picked up in the public opinion polls (Table 1). Two weeks before the referendum, the average of five polls from Essential, Freshwater, Newspoll, RedBridge, and Resolve showed No leading Yes by 60-40, the actual figure on the night.

Explaining the Outcome

What went wrong for Yes which began with a two-thirds majority support last year, reflecting generic goodwill towards the Aboriginal people?

In sum and putting it bluntly, instead of listening to people as they asked for clarifications and details and expressed doubts and uncertainty, the government and the corporate, intellectual, cultural, and media elites tried to lecture, bully, and shame them into voting Yes.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese accepted the activists’ maximalist demands in framing the referendum wording that requires a Yes or No answer to the three distinct questions on recognition, a new constitutional body, and additional powers to the federal parliament. He rebuffed the opposition leader’s efforts to negotiate a bipartisan question.

He rejected advice from Bill Shorten, a cabinet minister and former party leader, to first legislate a Voice body, enact recognition of Aboriginal Australians in the Constitution’s preamble, let people become familiar with the workings of the Voice and, if it proves successful and people’s comfort level with it increases, only then consider a constitutional amendment at that stage.

Albanese’s hubris was evident in the refusal to negotiate a sensible middle ground that could have seen recognition inserted in the preamble with cross-party consensus and a voice to parliament enacted by simple legislation that could subsequently be tweaked if need be and eventually repealed after its shelf life was over. Shortcomings were demonstrated also in rejecting calls to institute accountability mechanisms for the billions being spent on Aboriginal peoples and instead demonising anyone calling for an audit as racists. In the mixed messaging that described the referendum as ranging from a modest response to a warm and generous outreach from Aboriginal communities seeking a unifying moment of reconciliation, based on simple good manners, all the way to treaty and reparations.

There’s not one but several Aboriginal voices. With a total of 11 Aboriginal-Australians in the two houses, 3.2 percent of the population makes up 4.8 percent of members of parliament and senators. People soon wised up to ever-escalating and racialised demands for special treatment of the activists, their ingratitude for all the efforts already made and money spent to fund their self-serving agenda, and their responsibility for the policy mess that has done so little on the ground for Aboriginal children, women, and men in remote communities.

People were not convinced they should pay for reparations for things they did not do to individuals who did not suffer the harms. Instead, they were persuaded that the Voice would be the pathway to entrenching in perpetuity a victim mentality and the grievance industry. They feared that the politicians and the activists would use the new power, if and once granted, for self-interested purposes beyond the stated justification.

By contrast the No side kept its messaging simple, consistent, and disciplined. Their main talking points were reflected in the Redbridge poll that asked voters to rank their reasons for opposing the Voice. In order, the top three reasons were its divisiveness, lack of details, and that it won’t help Aboriginal-Australians.

As someone whose self-confessed animating passion in public life is the love of ‘fighting Tories,’ perhaps Albanese misjudged the initial overwhelming but soft support for the Voice as a good issue on which to wedge the opposition coalition.

Then there was the offence caused to growing numbers with the proliferating and endless acknowledgment of and welcome to country, the subtext of which is that the rest of us, from first to nth-generation Australians, can never claim Australia as our home but will always be guests instead. Ignoring the hardships of substantial numbers of European settlers and later immigrants and their sustained work to turn Australia into a prosperous and egalitarian democracy. The near-unanimous unity of the intellectual, cultural, banking, financial, and sporting elites in the condescending advice to prove our moral goodness by voting Yes. Albanese casting his lot with Qantas and its much-reviled former CEO in an especially egregious act of self-harm.

The No leaders made a virtue of the disparity in their respective war chests by several factorfold, describing it as the little people refusing to tug forelocks and instead standing up to the self-anointed superiors. Asked, ‘If not now, when?’, the people have chosen to send back the message: ‘Not now, not ever’ as far as departing from equal citizenship as the organising principle of Australia’s governance construct is concerned.

The Debate that Australia Had to Have

With the benefit of hindsight, this has proven to be the debate we had to have. For that we should be forever thankful to Albanese. Australians have rejected a policy that is premised on the stereotype that those with Aboriginal ancestry are something other than Australian who require special political privileges. This was a morally deficient model of recognition that attempted to reverse the singular achievement of the 1967 referendum that Australians are one unified people. We can now look forward to a fresh start to Aboriginal policy to address their stubbornly persisting real disadvantages free of the politics of victimhood and grievance.

Once the decision was made to put race at the centre of a brand new chapter in the constitution, the question of criteria for determining Aboriginal identity became unavoidable. It could no longer be shoved aside as irrelevant racism. More importantly, the debate registered the reality that many accomplished and articulate Aboriginal leaders who care passionately about the welfare of their people hold fast to an alternative, positive, and compelling vision. Its end point is a seamless blending of different ethnic groups into one national identity, but without losing their own.

People solidified a principled opposition to racial division and privilege that would have elevated one ancestry-based group over all others, and hitched it to cynicism about the practical outcomes projected to be delivered by presenting the Voice as a magic wand.

Moreover, the rising support for No emboldened more politicians and prominent Australians to come off the fence and also encouraged more citizens to speak up. As people realised that many others shared their views on the better and worse pathways forward, both morally and with respect to outcomes in redressing disadvantage, a self-escalating willingness to engage in the public debate and a self-accelerating fall in support for the Voice took hold. That is, the more that polls began to slide, the easier it became for more people to come out of the ‘deplorables’ closet, which then caused a further slide in the polls for Yes.

This was reinforced with the vitriol and abuse directed at No campaigners by many self-righteous, virtue-signalling scolds and sneers. Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price – who emerged as the one rock star of the campaign and the only one on either side with the elusive X factor – has been subjected to ugly, vicious, and racist bullying via voicemail (with callers obviously missing the irony of the unintended pun on Voice), as detailed in a Ben Fordham episode on 2GB radio on 25 September. Ironically, Price has emerged with strengthened authority and enhanced credibility while Albanese will be a much diminished PM.

The last desperate effort to convert the sceptical with the cynical attempt to guilt them into voting Yes backfired spectacularly. Many prominent politicians, Yes advocates, and media cheerleaders warned us that a No outcome will ‘confirm us as a frightened, insular nation’ (Chris Kenny, columnist with the Australian). The general reaction to this in letters to the editor and online and on-air commentary has been revealing.

People said such an outcome would prove that Australians still stand firmly for democracy and reject misguided attempts to divide our citizens by race; that we are not sheep to be tricked, simpletons to be swayed, nor cowards to be cowed into surrendering equality of civic citizenship as the most cherished principle and ‘one person one vote’ as the gold standard of democracy; if anything, in today’s culture of cancellation and abuse it takes courage to say no; that indeed the great unwashed have a better understanding of equality before the law than the sophisticated elites.

The campaign justified in the name of closing the gap has revealed instead the reality of a cultural chasm between city-based activists and the rest of the country. Maybe attention will now switch to working across the partisan divides to identity, enact, and implement policies to reduce the city-country gap (and a matching rich-poor gap) so starkly demonstrated by the vote. This means listening less to city activists and more to those living and working in remote communities.

Rather than being trapped in the prison of what happened over the past two centuries, Australians have chosen to look ahead and move forward together. Emotional abuse of the naysayers by the nattering nabobs of ‘positivism’ and the chattering intellectual and media class turned out to be offensive, off-putting, and counter-productive: who’d have thought? Or that the average Australian voter is smarter than the Prime Minister, even if that is proving to be not a very hard challenge?

In other words, Australians chose to vote No, not because they don’t care, but precisely because they do care, and care very deeply, emotionally and intellectually. They are not the frightened but the enlightened, committed to reinvigorating Australia as a unified nation and renewing the political project of a liberal democracy where the government stays in its lane and there is equality of citizenship and opportunity for all Australians.