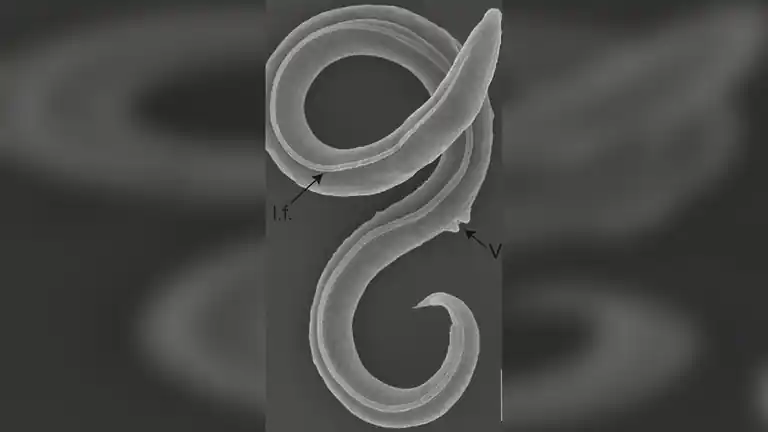

The microscopic organism belongs to a previously-undiscovered species.

Scientists in Russia have successfully revived a female roundworm that laid dormant in Siberia for 46,000 years. The worm sat in suspended animation for tens of thousands of years longer than any specimen studied to date, and began to have babies once thawed out.

The worm – a previously unknown species of soil nematode – was found in a soil sample from near the remote settlement of Chersky in northeastern Siberia, Russian Academy of Sciences researcher Anastasia Shatilovich wrote the current PLOS Genetics journal. Taken from 40 meters below the surface, the soil had not thawed since the late Pleistocene period, between 45,839 and 47,769 years ago.

Shatilovich’s team managed to revive the nematode, which then began reproducing via a process called parthenogenesis, which doesn’t require a mate.

While scientists have long known that certain species can survive essentially indefinitely by switching off their metabolisms, they have previously only been able to revive soil nematodes frozen for several dozen years. Efforts to revive other species have proven more successful, with the previous record set in 2021, when ancient bdelloid rotifers, microscopic multicellular animals, were resurrected after 24,000 years in the Siberian permafrost.

The nematode is no longer alive, but Shatilovich and her team have raised 100 generations from its offspring.

“By adapting to cope with extreme conditions, such as permafrost, for short periods of time, the nematodes might have gained the potential to remain dormant over geological timescales,” read an announcement from PLOS Genetics.

Siberia’s frozen landscape also hosts an unknown number of ancient viruses, one of which a team of researchers last year managed to revive after 48,500 years. Russia has warned that the continued thawing of the permafrost caused by climate change could unleash these dormant pathogens upon the world. Thawing soil that has been deeply frozen for centuries or even millennia could still contain “some viable spores of ‘zombie’ bacteria and viruses,” Nikolay Korchunov, a senior Russian representative at the Arctic Council, told RT in 2021.