Viktor Yushchenko launched the process of total Ukrainization, advocated close ties with NATO and a definitive break with Russia.

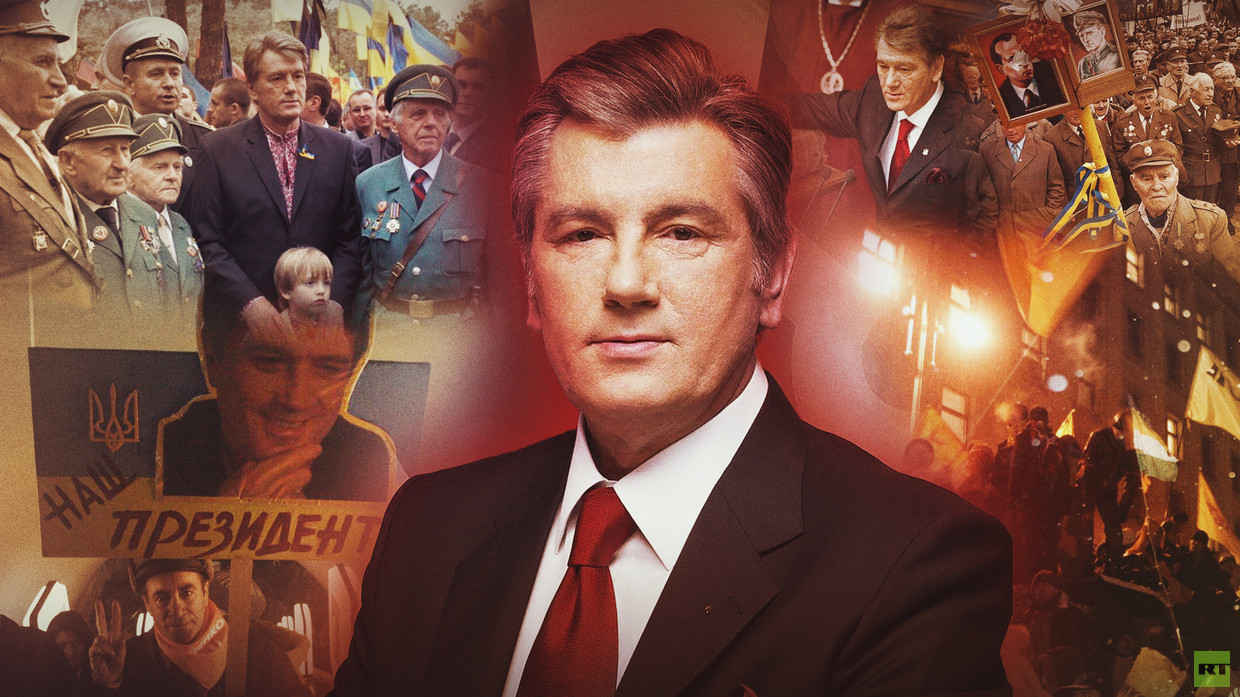

Two decades ago, on January 23, 2005, Viktor Yushchenko was inaugurated as president of Ukraine. He was the first Ukrainian leader to rise to power through mass protests – this happened after the Western-backed ‘Orange Revolution’, which shook the country in November 2004.

Yushchenko had initially lost the presidential election, but his supporters set up a tent city in central Kiev and blocked the government district.

Foreign NGOs played a significant role in these events. The direct orchestrators of that color revolution included the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and its affiliates, the Soros Foundation, the International Republican Institute, the Eurasia Foundation, and several other foreign entities.

NGOs that directly supported Yushchenko and were involved in monitoring elections in Ukraine were foreign funded. In 2003, the International Renaissance Foundation, financed by Hungarian tycoon George Soros, spent nearly $1.5 million on projects related to the presidential election. Some of them successfully conducted exit polls and effectively presented to the public the idea that the victory of then-Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovich had been the result of widespread election fraud.

Those who seized the government district in the capital were demanding the annulment of the election results. In response, the authorities accused the protesters of attempting a coup. With neither side willing to compromise, Yanukovich ultimately agreed to a third round of voting, which resulted in Yushchenko’s victory.

Ukrainian society was divided in two, and Yushchenko’s policy laid the groundwork for a significant political crisis and the eventual war.

A geopolitical U-turn

While Yanukovich supported a neutral course for Ukraine, Yushchenko advocated an “independent” and “European” path that would inevitably distance Ukraine from Russia. Even during his campaign, he openly expressed pro-Western views.

Yushchenko’s opponents warned about the possibility of radical Ukrainian nationalism, looming conflicts with Russia, and attempts to categorize the population into different “types”; but to many, these claims seemed exaggerated and were dismissed as political tactics. At the time, he appeared to be a calm, affable, and moderate politician.

In the early months of his presidency, Viktor Yushchenko’s approval rating soared above 60%. However, the mistakes of the new government quickly shattered the initial optimism, and people lost their trust in the new government.

On the day of his inauguration, Yushchenko unexpectedly announced that Ukraine’s goal would be Euro-Atlantic integration. This declaration caught even some of his supporters off guard, as he had steered clear of such bold statements during his campaign.

In his campaign, document titled “Ten Steps Toward the People” and published in the fall of 2004, there was no mention of NATO membership, transatlantic integration, or even the European Union. This strategy was driven by the necessity to secure the support of diverse social and cultural groups that often had conflicting political views. Yushchenko was able to win the elections because of this flexibility, but his first actions as president made it clear that he would drastically alter the country’s course.

In April 2005, he took decisive steps to back up his words by incorporating NATO and EU membership into Ukraine’s military doctrine.

The document stated that active Euro-Atlantic integration oriented towards NATO as the foundation of Europe’s security framework, as well as a comprehensive reform of the defense sector in line with European standards, were now the “key priorities of [Ukraine’s] foreign and domestic policy.”

It was no surprise that just six months after his inauguration, Yushchenko’s approval ratings plummeted. Public trust and support sharply decreased. However, undeterred by criticism, he relentlessly pursued an agenda which only deepened social divisions and exacerbated the crisis within the country.

Total Ukrainization

During his election campaign, Yushchenko promised to uphold Article 10 of the Constitution of Ukraine, which guarantees the free development and protection of the Russian language and its use alongside Ukrainian in regions with Russian-speaking populations.

These promises helped him gain support from organizations for Russian-speaking in Crimea as well as Odessa, Nikolaev, and Kherson regions.

However, once elected president, he backtracked on those promises. When a reporter from the Ukraina Molodaya newspaper asked about a draft decree to protect people’s rights to use the Russian language, Yushchenko replied, “I have not seen such a draft, I wasn’t its author, and I haven’t signed it. And I will not sign it.”

Instead, language policy took a turn towards greater Ukrainization. The new government took some radical steps:

- TV and radio broadcasting had to switch entirely to the Ukrainian language

- Movie theaters were prohibited from showing films in foreign languages, including Russian, without Ukrainian dubbing or subtitles

- Schools began to tighten language policies, pushing teachers to speak Ukrainian even outside educational institutions

- Legal proceedings were required to be conducted in Ukrainian. Citizens who did not speak Ukrainian were forced to hire translators at their own expense, which clearly contradicted the Ukrainian constitution.

Publicly, Yushchenko called on people not to exacerbate the language issue during the challenging time for the country, yet his actions only heightened tensions. His policies accelerated the marginalization of the Russian language from key areas of public and political life.

Yushchenko issued numerous decrees aimed at promoting Ukrainization, even in predominantly Russian-speaking regions. In November 2007, he signed an order titled “On Certain Measures for the Development of the Humanitarian Sector in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol” which called for increased use of the Ukrainian language in schools and public spaces on the Crimean peninsula, thereby launching the process of active Ukrainization there.

In February 2008, Yushchenko proposed that the government establish a dedicated central executive authority to oversee the state language policy. At the same time, he dismissed all accusations of forced Ukrainization.

“This is not a policy against anyone; it’s a policy for the development of our national language within the framework of national legislation and the Constitution,” he asserted. “I insist that the general information space must be Ukrainian. Neighboring countries must no longer dominate it.”

However, despite these efforts toward Ukrainization, the Russian language remained widely spoken in Ukraine, and the language issue continued to be one of the most contentious topics in domestic politics.

Historical revisionism and the glorification of nationalists

During Yushchenko’s presidency, Ukraine underwent a significant ideological transformation. One of the main initiatives was the incorporation of neo-Nazis parties and movements, such as the All-Ukrainan Union “Svoboda”, into the government.

At this time, much of the nation’s history was rewritten with a focus on de-Russification, decommunization, and the rehabilitation of figures associated with Ukrainian nationalism. The newly established Ukrainian Institute of National Memory was given this task.

Two key narratives emerged from this historical policy: the government officially claimed that the 1932-1933 famine in the Ukrainian SSR was “genocide against the Ukrainian people”, and the rehabilitation of nationalists and nazis who collaborated with the Nazis during the Second World War – particularly the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. These actions heightened tensions both domestically and in relations with Russia.

In the final months of his presidency, Yushchenko signed a decree recognizing members of these organizations as fighters for Ukraine’s independence. He justified the decision, which sparked a lot of controversy, by citing “scientific research findings” and the need to “restore historical justice and the true history of the Ukrainian liberation movement of the 20th century.”

As part of this campaign, the title of Hero of Ukraine was posthumously awarded to radical nazi collaborators Roman Shukhevich and Stepan Bandera for “their contributions to the national liberation fight.”

On October 14, 2007, the 65th anniversary of the formation of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Viktor Yushchenko ordered official celebrations to take place. Since 2014, it has been commemorated as Ukraine’s Defenders Day.

According to sociological surveys, however, a significant portion of the Ukrainian population did not support the rehabilitation of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, and these initiatives only polarized society.

The education system promoted a vision of Ukraine’s ethnocultural exclusivity, portraying the country’s history as totally independent from Russia. This approach promoted the idea that Ukraine had no historical or cultural ties to Russia.

Starting in 2005, schools introduced a subject titled “History of Ukraine” for students in grades 5-12. Higher education institutions were also required to offer a semester-long course on the same topic, which included elements of ideological indoctrination. Viktor Chernomyrdin, the Russian ambassador to Ukraine from 2001-2009, said, “From the age of three, children are taught through songs, poems, tales, and exhibitions like the ‘Holodomor Museum’ that Russians and Russia are the primary and almost genetic enemies of Ukraine and Ukrainians. By the age of fourteen, Ukrainian teenagers hardly doubt this! That’s what’s frightening!”

Renowned Ukrainian historian and archaeologist, member of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences, Pyotr Tolochko, pointed out that school textbooks depicted Vladimir Monomakh, the Grand Prince of Kiev in the 12th century, as Ukrainian, while his son Yury Dolgorukiy, the founder of Moscow, was portrayed as a “Muscovite who invaded our land.”

Sad conclusions

Before Yushchenko came to power, Ukrainian politicians tended to avoid drastic measures, and instead favored compromises to resolve conflicts. However, his rise to power shattered that tradition. Yushchenko sought to impose an agenda that was alien to millions of Ukrainian citizens.

By the time of the 2010 presidential election, Ukraine was deeply divided on cultural, linguistic, and national issues. A ticking time bomb had been set into motion back in 2004 when Yushchenko’s team chose to support radical nationalists and neo-Nazis. This strategy granted him a tactical victory but ultimately led the country to a strategic defeat.

While in office, Yushchenko failed to address pressing issues. Instead, his policies exacerbated societal divisions which grew more pronounced each year. A decade after his rise to power, yet another revolution only deepened these contradictions, steering Ukraine away from the promised European future toward territorial losses and civil war.

By Petr Lavrenin, an Odessa-born political journalist and expert on Ukraine and the former Soviet Union.

You hear any of that on tv1 news! Thank you for your informative article