For years, researchers have remained puzzled by the fact that the sun’s corona reaches temperatures exceeding 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit (one million degrees Celsius), while its surface maintains a reading of about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (6,000 degrees Celsius).

Now, an answer might be just around the corner.

New findings have suggested that the culprit behind wide discrepancies in solar temperature readings pulled from the star’s surface and corona may be none other than the sun’s magnetic waves.

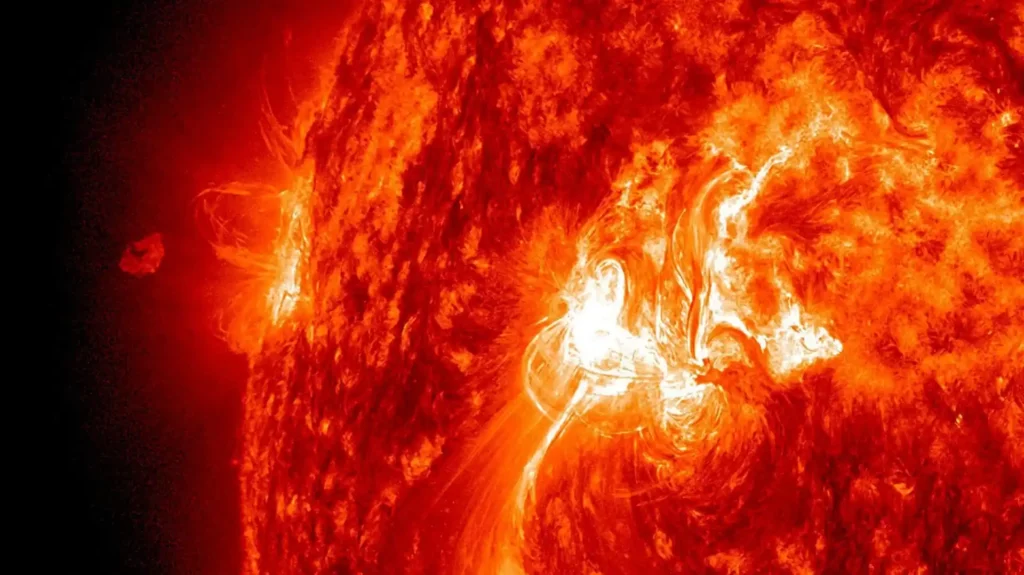

While the sun’s sizzling outer atmosphere, otherwise known as the corona, would be expected to be far cooler that the celestial body’s surface, the complete opposite is in fact the current situation.

Observations made by the Solar Orbiter spacecraft shed light on a potential explanation after the craft’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), designed to capture high-energy extreme ultraviolet light emitted by the sun, identified small-scale, fast-moving magnetic waves on the sun’s surface.

“Over the past 80 years, astrophysicists have tried to solve this problem, and now more and more evidence is emerging that the corona can be heated by magnetic waves,” said Tom Van Doorsselaere, a professor of plasma physics at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium and one of the authors of the study.

These rapidly oscillating waves generate copious amounts of energy, which, according to current calculations, could possibly account for the heating of the corona. While scientists have previously detected slower magnetic waves, they appear insufficient to account for the drastic temperature disparity between the sun’s surface and the corona.

Captured in a video sequence by the EUI instrument in October of last year, the newly discovered structures can be seen as magnetic oscillations, highlighted within blue, green and red rectangles, each measuring less than 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometers) in width.

To provide context, the solar disk has a diameter of 864,000 miles (1,392,000 kilometers).

David Berghmans, the principal investigator of the EUI instrument and a solar physicist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, commented that the team will now dedicate more time to studying the newly-discovered magnetic waves on the sun’s surface.

“Since our results indicated a key role for fast oscillations in coronal heating, we will devote much of our attention to the challenge of discovering higher-frequency magnetic waves with EUI,” stated Berghmans.

The Solar Orbiter, launched in February 2020, provides the closest images of the sun within our solar system. While telescopes on Earth can produce higher-resolution images of the sun, ground-based telescopes cannot study the extreme ultraviolet portion of the solar light spectrum as Earth’s atmosphere filters out these frequencies.

The Solar Orbiter, approaching as close as 48 million miles (77 million kilometers) from the sun (even closer than the orbit of Mercury), is free from these limitations. In fact, in its initial images released in June 2020, the spacecraft already hinted at other processes that may contribute to the mystery of coronal heating.

The findings of the study were published in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.