It’s a week where junior doctors are on strike, and strike they should. But it’s bigger that. Should you care if your local doctors’ clinic is not owned locally and independently? Should your local MP care? I believe we all should care.

There’s increasing evidence that a corporate model of practice management in general practice (GP) clinics do not, – and cannot – help patients or doctors. To put it simply, the corporate model is not in the public interest. But doctors are being forced to sell – and the only way it works is a high volume, slim margin numbers game. Just like junk food and fizzy drink.

Medical clinics in New Zealand have never been ‘left to the market’. The government through subsidies and regulations, control medical clinic income levels. But the government has failing to adjust their policies to reflect surging rates of chronic illness (mental and metabolic), red-tape, and interest rates. GP clinics are not just sitting, like the proverbial frog in boiling water, the government is covering the pot with a lid.

Imposed austerity and programmed failure tumbles through the GP clinics, through the emergency ambulance service and into the hospitals. Junior doctors are on strike this week. But the financial implosion in GP clinics is directly related to pressure in the hospital system.

This complex cocktail of over-regulation, fees that haven’t been permitted to track with inflation, and rapacious interest rates, are forcing doctors to move away from the care-based ‘traditional model’, where the doctor-patient relationship is upheld, to numbers-based systems that prioritise high volume, low margin turnover. Owners of practices operating traditionally – possibly between 20-30% of practices across New Zealand – are taking out second mortgages, it’s the only way they can keep practices going.

What is happening here?

Forty to sixty percent of clinic costs go to GPs income. Then there is the cost of staff, overheads and practice expenses. Then there are the compliance costs that are necessary if doctors are to receive government funding. The compliance policies are onerous and they add up. It’s not just the costs to set up a doctors practice and adhere to specialist building codes; it’s precise requirements for clinic policies for a broad range of issues: from important factors such as fire drills and waste disposal, to silly rules directing where gumboots go, and so on. The problem for doctors’ clinics, is if they don’t pass the complete audit for every little bit of paper, they can’t get capitation.

Most income into doctors’ clinics comes from capitation and fees.

Capitation is the funding from the government per person enrolled in the clinic, by age group and gender. Medical clinics will receive more per person for the very young, and the very old, and less in the middle years. They’ll receive extra money for vaccination. Capitation is not based on number of patients visits, but on numbers of people registered with that clinic. Capitation is received – whether a person is seen by a doctor or a nurse.

Then clinics can set their own fees. But fees are capped, annual fee increases are limited to 1% – far below inflation.

Doctors are having to take out a second mortgage – particularly in the poorer regions where visits extend far beyond the level of government funding provided.

It’s a slow-motion car crash. The sickness of the population – the costs of caring for superadditive multimorbidity and the complexity of the conditions being presented to doctors. Financial precarity, – have dovetailed, overwhelming and engulfing current capitation rates.

In the mess private equity companies, with a swathe of efficiencies swoop in, usually when a partner is about to retire.

Corporations owned by foreign investment companies, keep an eye on when doctors reach retirement age. They then step in with a generous offer. The exhausted owner has little choice, if existing partners can’t compete with the generous offer.

The corporate model runs on high turnover and slim margins. Like fast-food and $2 dollar shops, it’s a numbers game. You own a lot of medical practices, you accrue a lot of profits. The only way it can work is to cut staff, allocate all appointments to the next available doctor or nurse and increase patient turnover. People are seen by whomever is on a shift.

When corporates step in, they depersonalise medicine.

These corporates get the practice to open the books. They then strip out excess staff. They increase the serviceable number of patients seen by a single doctor from the norm of 1,300 or 1,400 to 2000. They achieve this by shifting patients away from their ‘family’ doctor; by increasing the volume of lower wage prescribing-capable nurses seeing patients in comparison to doctors (remember, capitation rates don’t care who sees you). They fit all patients in to see whoever doctor or nurse is free, and increase wait times to see a doctor, ensuring there is no wasted minute of the day.

The practice owner, a doctor who is selling, is required to work there for three years, to ensure that that doctor does not leave to start a new clinic, and take patients with him/her.

In other words, it’s just a utilitarian numbers game.

In order to achieve the 2,000 case load, doctors have to see a certain number of patients. These doctors get a monthly statement which reports their ranking. The problem is that female doctors see less people per day. Female doctors see the complex cases. The social, emotional, the battered, the depressed. They take longer with these patients. Dr Bruce sees 25 patients each day, while Dr Sarah sees 15 patients per day.

Female GPs are battered by the corporate model. Their throughput is lower – they’re not valued. They get disheartened, exhausted, they have to take stress leave.

This is the pattern, observed by doctors and clinic staff, when the corporates take over.

Kiwi GPs have been trying to get the government to listen, and improve capitation rates, but, as one GP told me, it’s like ‘pissing into a storm’. The submissions fall on deaf ears.

The problem is worsened by the around $65-75, 15-minute consultation period, which erodes to, by the time the niceties are over, a 7-minute consultation. Ten bucks a minute. No-one gets better, there’s only time to prescribe more medicine as their body domino-like tips into more and more multimorbid problems.

The diabetes, the inflammation, the mental health, the inflammation, the fatigue, the frailty all tip into each other, resulting in drug cocktails not just for the conditions, but to manage the drug side-effects. Doctors don’t have time to work with patients to address social, psychological and economic drivers of disease, nor support the patients over time to reverse their (all too often diet-driven) conditions.

The 7-minute consultation, when it merges with a numbers-based operational strategy, exacerbates inequities because there is no time for the sickest and the poorest. The sickest and the poorest are often isolated and alone. Doctor-patient relationships cannot develop, yet relationships are key to trust-based doctoring and the practice of informed consent.

There has been an accelerated shift away from local ownership in recent years. New Zealand’s largest players are Tamaki Health who is 50% owned by Australian private equity firm, Mercury Capital, and the New Zealand stock exchange listed Green Cross Health (who might be vulnerable to takeover anytime soon). Tamaki has nearly 50 medical clinics, while Green Cross Health has 63 medical clinics.

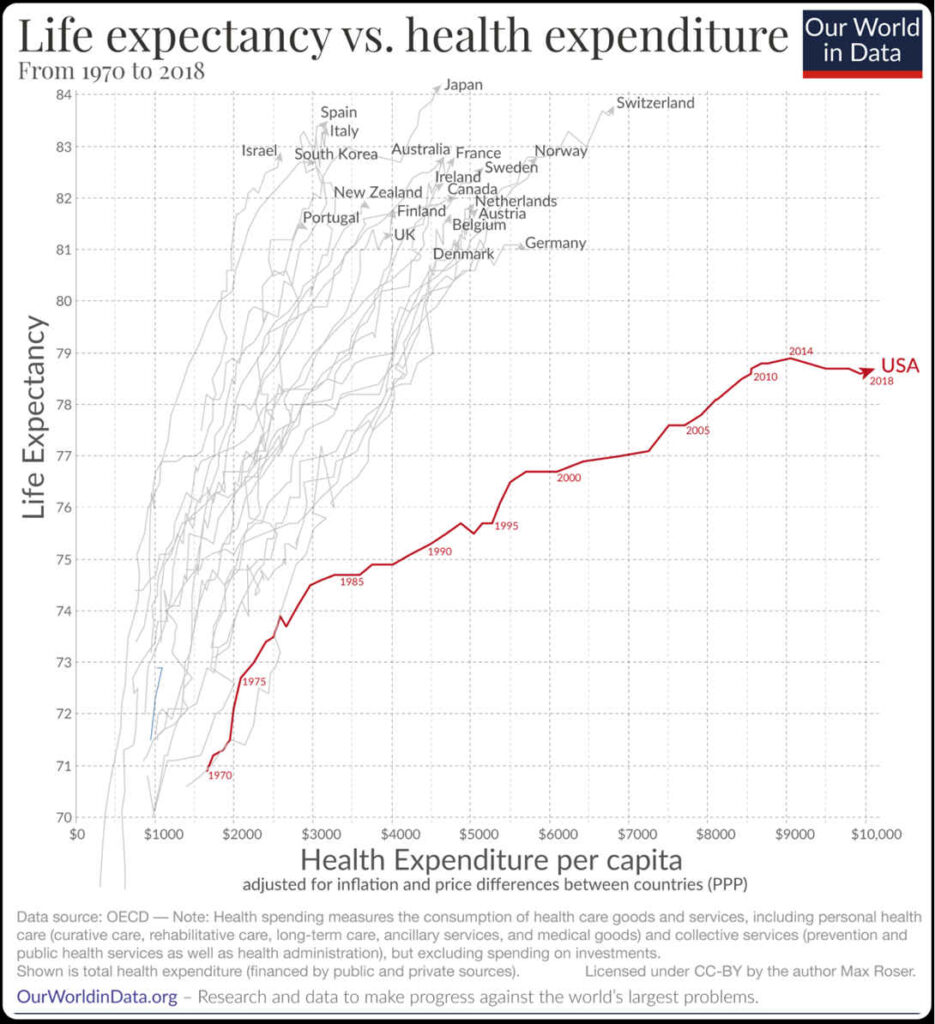

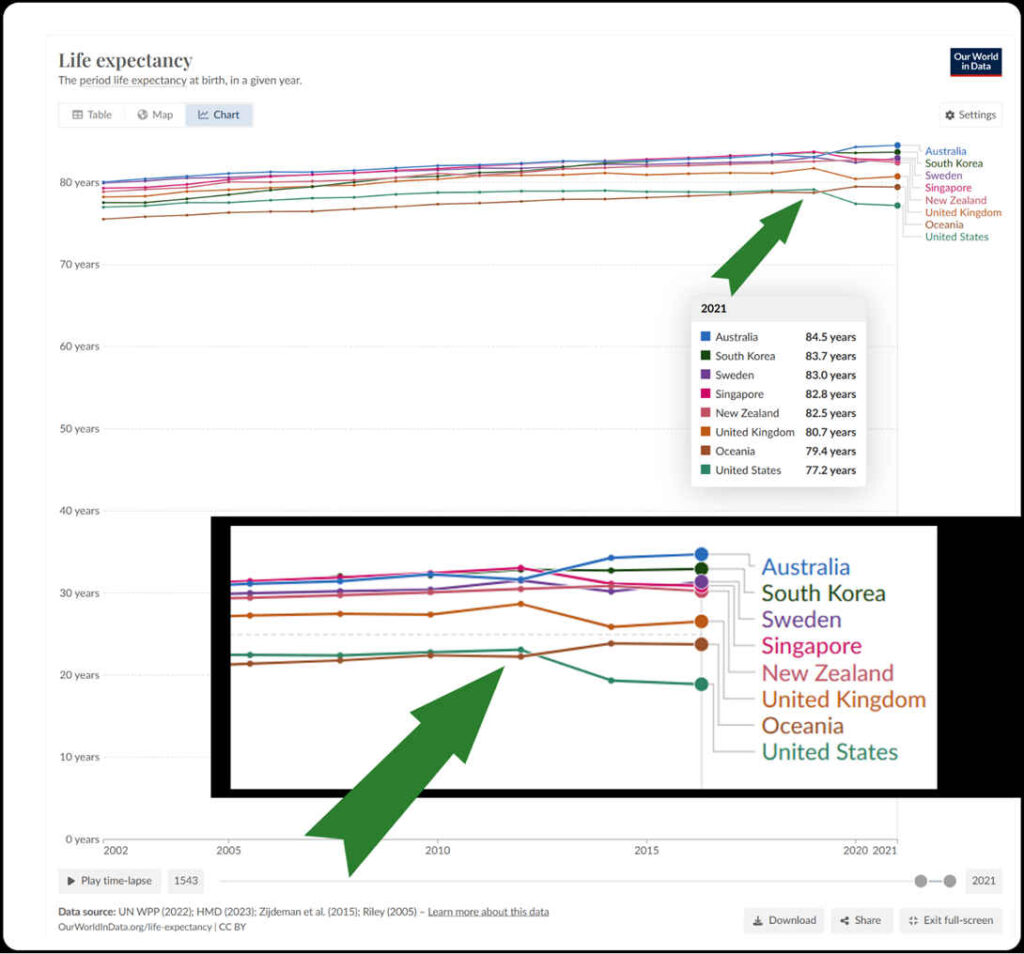

The corporate recipe is one that America knows well and the failure is writ large in terms of the United States indebtedness, inequality and health statistics.

Life expectancy is a key indicator of national health. The United States scores outrageously badly for such a wealthy country. In the U.S. the average period of life expectancy has never exceeded 80 years.

Life expectancy isn’t just a factor of medicine – it strongly associates with not just the wealth of a country – but a relative absence of poverty and indebtedness. In the U.S. the poorest 50% of people only own 2.5% of wealth.

Health expenditure in the U.S. equals some 19% of GDP compared to New Zealand’s 10%. Last year I went to outpatients in the United States, it cost USD200 to see a person who wasn’t a doctor.

The US is ahead of the game when it comes to corporate take-overs of GP clinics. The same drivers – financial stress, force doctors to sell:

‘four of five physicians indicated the need to better negotiate favorable payment rates with payers was a very important or important reason in the sale of their practice to a hospital or health system. Next were the need to improve access to costly resources and the need to better manage payers’ regulatory and administrative requirements.

Each was flagged by about 70% of physicians as a very important or important reason.

Between 2012 and 2022 the share of physicians working in private practices fell by 13 percentage points from 60.1% to 46.7%.’

Yet even the high volume, low margin business model is failing in the home of cheap and fast corporate medicine.

Ironically, Walmart, after launching Walmart Health in 2019, and promising that healthcare Walmart would make primary care accessible and affordable, has recently done an about-turn and closed 51 health centres across 5 states. While the pharmacy business remains profitable, primary care is not, due to, as Walmart stated:

‘[t]he challenging reimbursement environment and escalating operating costs create a lack of profitability that make the care business unsustainable for us at this time.’

Of course, the decision by governments to underfund public assets and public services – particularly in the health sector – is game that remarkably favours large corporate entities.

It is the neoliberal game of socialising the costs (as government still pays capitation, benefits and subsidises pharmaceuticals) and privatising the profits. Doctors and their patients with multiple health conditions site at the arse-end of the neoliberal game.

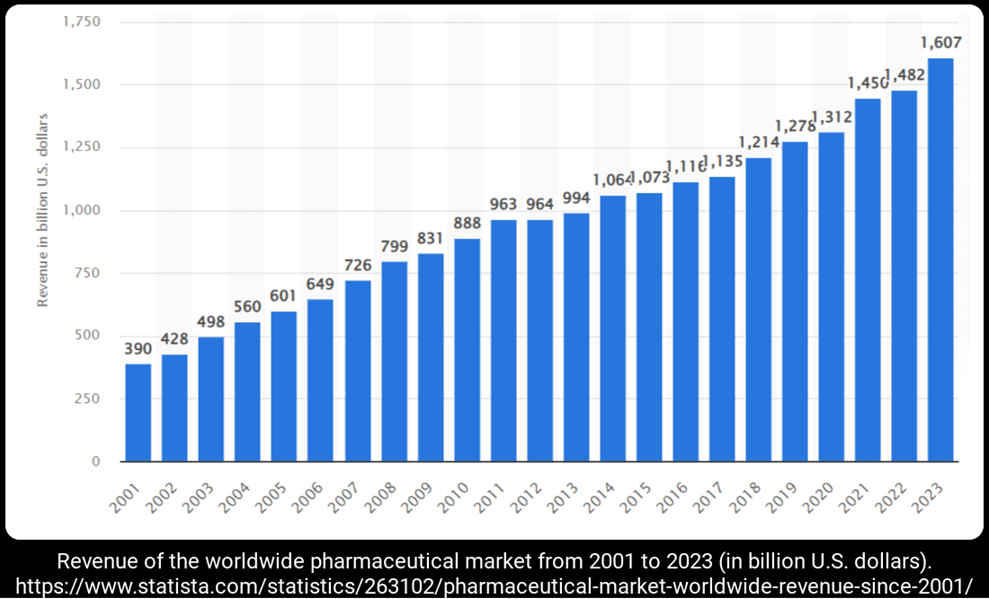

Doctors are highly stressed wage-earners with little autonomy. Patients suffer as government agencies fail to be curious and fail to acknowledge the dietary drivers of disease. The government declines to mitigate the predatory cunning of the food environment and increase access to safe and nutritious food while boosting Pharmac funding to $6.3 billion.

Instead of time to address the drivers and support patient-led change, the problems are medicalised. This situation works perfectly for the pharmaceutical companies that supply Pharmac. Globally, drug companies seem to be doing rather well.

In parallel, as illness climbs, governments commensurately fail to sustain investment in health services, while turning a blind eye to outrageous failures of capitalist health care. Corporate numbers-based medicine, like hamburger franchises, only becomes ‘efficient’ through inevitable rounds of monopoly that consolidate these industries.

Inevitably as market power consolidates under oligopolistic industry ownership structures, these corporations increase prices, simply because they can. There is very strong evidence that when private equity firms step in medical fees don’t decline. A recent United States (U.S.) report Monetizing Medicine, highlighted that acquisitions by private equity firms result in price increases. When a private equity firm controls a competitively significant share of a local market, price increases are exceptionally high. Private sector companies are incentivised to exploit loopholes and increase income in a way that smaller firms, or the public sector are not.

If we keep thinking in parallel – over this same period – a god-trick has been played where governments undermine and obfuscate the role of fiscal policy in resourcing public infrastructure, wages and services.

Wrapped in a ‘there is no alternative’ rhetoric, this language has worked a certain kind of magic. The magic is that the nation state is pivot of government officials to crafting policy and legislation to ensure corporations can occupy the space left vacant by the state. Where officials were previously charged with developing and controlling assets, information and services that previously were held in common for a public purpose.

Instead of government agencies and public employees, large corporations and their employees insert themselves as stakeholders in public consultations and co-develop public policy. As the knowledge and interests of large institutions aggregate there is a transfer of power – of the relations of power.

With the government pretending that fiscal policy cannot be used, personal debt accrues, education and health declines, along with a precarious, undernourished, rentier society. It’s no longer magic but dependence and a decline in human agency, creativity and productivity. Increasing frailty and years lost to disease, where the only ‘scientific’, legitimate solution provided by the state is layered medication.

The narrowing number-based agenda fails hospital doctors, GPs, and resolutely fails their patients.

Who else is failed by this blinkered economic policy? Have a yarn to your friendly ambo.

‘Ambulance call outs in NZ have risen by 51% over the last 9 years with only 8-10% classed as high acuity or what we would call real emergencies. That leaves 90% of visits that theoretically could be dealt with by the patients GP.

People still expect to have a back door into the emergency department if taken by ambulance, this is definitely not the case. Patients are triaged following the same process as if a patient turns up at the public entrance. So often calls to the ambulance will result in many hours spent in the waiting room.

Calling an ambulance also is not cheap, it costs $98 for any medical visit, usually way more than a GP visit but probably less than an urgent care clinic. Patients also struggle with access to transport and other social issues such as care of dependents or other family members. The future of ambulance care overseas is following the same pattern with specialist paramedics turning into community healthcare workers, assessing and treating people in the home. The difference being that that ambulance service is funded by national healthcare as opposed to in NZ. There is minimal funding for similar in NZ.’

The failure of the government to increase capitation means that people will wait 5 hours in a waiting room. Ambos have their regulars that prefer the costs of an ambo visit particularly when they struggle with transport. And although St John might have a quarter of a billion in equity, they appear to run on rather fine margins. I.e. there’s not much capacity to expand.

Who’d be a general practitioner? Facing declining wages, no prospect of coaching patients over time and limited capacity to own a clinic, it’s no wonder young graduates select higher-paying specialities, head off-shore or drift into other public work. Anything other than general practice.

Corporate medicine severs long-term relationships that are nurtured over years, that foster a relationship and promote trust, between doctor and patient.

As one doctor said to me:

‘The prevailing approach focuses the doctor-patient interaction on isolating a symptom/disease/therapy triad. This approach largely ignores the causation of the patients presenting symptoms and instead focuses on labelling the symptom/disease complex for the purpose of assigning a therapeutic product. This is a teleological approach as this product is overwhelmingly supplied by the medical-industrial complex that profits from this model and which also directly or indirectly controls medical research, medical publishing, medical education, medical regulation and the scope and nature of medical services in most countries, as was so clearly evidenced with the Covid experience.

A patient centred approach would identify the presenting symptoms as indicators of a loss of balance in a complex, dynamic living system, a human being in their social and physical environments. It would then explore the multiple influences that could perturb or support system balance in that person in their environments.’

Humans need relationships to compassionately navigate tough years, to navigate mental and metabolic illness, often together. Humans need a caring, respectful infrastructure which promotes autonomy. Autonomy is essential to owning a health pathway and preventing patients dominoing into worse disease.

‘The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.’ – Sir William Osler

The technical biomedical paradigm undermines the reality, that doctoring is both an art and a science. Humans are biological, spiritual, social beings and our bodies react to the world around us.

Patients might come in with social, cultural, economic and environmental drivers of disease. A biomedical paradigm considers it morally appropriate that treating a patient’s symptoms is all that is required for doctoring. The ethics of this paradigm presumes that polypharmacy is appropriate, and that side effect amelioration is perfectly suitable. That the uncertainty of which side effects and which drugs which might deal with that are an acceptable science-based uncertainty. But it fails to acknowledge other uncertainties, such as what might happen with comprehensive dietary shift away from ultraprocessed food. Yet from the Ministry of Health to clinical medicine – this latter prospect is an unacceptable non-science-based uncertainty.

The biomedical paradigm presumes that one doctor is also the same as the next. That doctor no. 1234 is interchangeable with doctor no. 4321. Patient Smith is interchangeable with Patient Green. No matter the curiousity, the agency, the personal experience of that doctor.

As another GP stated to me:

‘It pretends that no matter how frightened, demented, disabled, crippled, over medicated, over-protective – patients and their families are, one interchangeable doctor is just as good as the next.’

As Jodie Bruning, my number, in this paradigm, turns me into a number, an object – to be technically administered. Dealt with. In the words of Martin Buber, instead of I and Thou, I become a number, an object, an ‘it’.

No matter that my health condition stems from the toxic triad of chronic infection, toxic metals or electrosmog; from abuse or malnutrition – these drivers are not to be recognised. Funding for testing and research toxic exposures are denied, and funding from ACC to heal from the toxic exposures is to rebutted. Instead, the symptoms are to be medicated. That a young person is systemically undernourished and that their diet promotes inflammation and/or mental illness – the symptoms are to be medicated.

A person is more vulnerable to infectious disease because they are inflamed and undernourished? There is an injection for that. And the healthy patients can have it too.

What will happen in the future? The biomedical paradigm seems to presume that doctors will become largely redundant, that robots and AI will step in, that the market will ‘provide’. The biomedical model presumes that medicine will always fix the issue. And then another medicine will fix the next issue. That telehealth will provide equal care to a visit in a doctors’ clinic.

The biomedical paradigm is fostered and nurtured by oxymoronic rhetoric that promises inclusivity and equity and claims data is King, while sidelining the nutritional, social, corporate and environmental drivers of disease. Biomedical, data-driven paradigms obfuscate and pretend that obligations of active protection to Māori will be fulfilled simply by equity of medical treatment.

The biomedical paradigm is nurtured by a media that fails to critically question counter-intuitive claims that all will be treated equally and get equal medicine. Theres no language to address the wild contradictions, the writing-out of human agency, communication and relationships.

In the future technical inclusivity is more important than compassion and heart-based connection. Theoretically, advances in genetics, artificial intelligence and increases in mandatorily administered vaccinations will improve all patient outcomes.

In budget month, how do we fix this?

Capitation rates can increase. The perverse incentive of failing to suitably increase capitation rates, of failing to permit patients to see a doctor with whom they have a relationship, of working doctors into the ground, of presuming all conditions are treated equally can stop. Funding can expand for community-care provided by specialist paramedics or by registered nurses with prescribing authority.

But don’t listen to me, ask your doctor.

Image credit: Unsplash+

The globalist neo liberal sell outs running NZ want to move us to an Americanised model. Heck we are almost there now with people like myself taking out private health insurance, on top of excessive taxes we pay for healthcare we don’t receive.

My family are considering leaving and we are, I’m sure, not alone. Australia’s healthcare is leagues ahead of ours, cancer for example, is five times more survivable there than here (those are NZ govt figures by the way) and their system is hardly perfect, either.

Another excellent article Mrs B. My mother was on the front line when our medical system became monetised, and she hated it. It all became about balancing the ward ‘budget’ and a difficult patient who needed expensive meds would cost you too much. (And we pay WAYYYY too much for our pharmaceuticals as well – I guess that’s another story) NZ was always so proud of its “socialised” medicine where we all got what we needed “for free” – now we have four tier medical system – public, private, ACC, and now the Maori system (sorry can’t remember what we call it) So a rugby patient with a torn ligament will get immediate surgery through ACC, but someone suffering with a completely stuffed degenerative arthritic knee will have to wait months/years for a knee replacement. The wealthy/middle class pay health insurance and get what they need, when they need it. I don’t like the unfairness in the system, and i don’t like the injected stupidness in the system either – we end up with the worst medical system we could have, the same way we end up with the worst financial system that we could have. When we run the country to benefit corporations, it’s all down hill. And yet people i know rail against “socialism in New Zealand” and I have to keep reminding them, what they (the govt?) are doing is not “socialism”, (like you said “socialising cost and privatising profit” ) it’s corporatocracy, and its tyranny because they get to control the health care system and dictate what health care people can and can’t have. try getting a vit C injection in Waikato Hosp even though it’s on record their as being a life saver for example. And the Govt is essentially at war against the people of this country, by making deadly medicine, the main, the funded medicine. does my head in! it’s a quiet war that not many are paying attention to.

To study medicine nowdays and become a doctor is part of a ” carriere plan”. They are only interested in money, not in patients. And it should be said that many are totally incompetent and dishonest about the made mistakes: that include women