The Philippines has a vital trade relationship with Beijing, but Washington sees it as a staging ground for potential Taiwan hostilities.

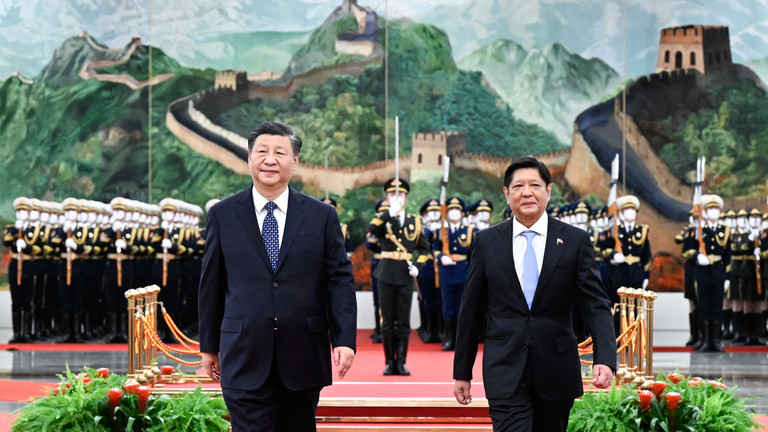

Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the president of the Philippines, opened 2023 by making a visit to China. There, 14 bilateral agreements were signed between Manila and Beijing.

Between the two, this sort of diplomacy is not unusual. They are close economic partners, with China being the Philippines’ largest export market and a critical source of inbound investment, especially as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The two countries have some disputes, of course, especially when it comes to the South China Sea, but they have elected not to allow that to spoil the bigger picture of bilateral relations, at least for now.

But there is one elephant in the room which haunts Manilla’s ties with Beijing, and that is the country that perceives itself as the true and rightful master of the Philippines – the United States. Even as Marcos Jr. develops his cooperation with China, the newly elected president is facing considerable pressure from Washington to allow it to increase its military presence in the country, and potentially get roped into a potential Taiwan contingency, owing to the Philippines’ critical geostrategic position. This has led the foreign policy of the archipelago country to become a tightrope balancing act, which could easily plunge it into disaster if something goes wrong.

The Philippines is a staple of American power in the Asia-Pacific. That’s because it bears the dubious distinction of being the only country in Asia to have been a literal colony of the US. Once a dominion of Imperial Spain, the islands were annexed by Washington following the Spanish-American War of 1898. The war was what allowed the US to become a great power in the Pacific, and the Philippines would remain in its possession until after the Second World War, with the US having fought off a Japanese invasion of the islands.

Having become independent, the Philippines naturally became a US ally. As a series of islands located off South East Asia, the country allows the US to project military power onto the continent – for example, by using its naval bases during the Vietnam War. Situated just to the north of the islands is Taiwan and Mainland China. Given this strategic value, the US sees the Philippines as a critical piece on the board for any future conflict against Beijing. The islands are essential to stopping China from realizing its claims over the entirety of the South China Sea and fighting back against a Taiwan contingency. The US could not have made that clearer in its recent overtures to Manilla.

But it isn’t that simple. Although the Philippines has grievances with Beijing over contested territory in the South China Sea and has been instinctively pro-US for its recent history, the reality is that it’s also a poor country, and alignment with the US doesn’t alleviate that. The Philippines needs an export market, it needs infrastructure investment and it needs Chinese tourism. China is not just a neighbour, but the best-positioned country in the world to provide all of these things. This has made the bilateral relationship stable, despite moments of tension over the South China Sea.

And as a result, the Philippines does not behave in its foreign policy like an overt ally of the US, in the way a country like Japan would, but rather seeks to carefully hedge itself between Washington and Beijing. This realignment of the Philippines’ foreign policy began with the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte in 2016, who sought to assert the country’s geopolitical autonomy by more actively courting China, while keeping Washington at arm’s length.

This was because Duterte’s understanding of what constitutes national interests – his approaches to issues such as crime, as well as the economy – did not align with America’s vision. Although Duterte did not throw out the US completely, as evidenced by his decision not to terminate the ‘visiting forces agreement’, he positioned the country so it might not become a US proxy against Beijing, and understood China was useful in some respects as a partner.

It is perceived that newly elected president, Ferdinand Marcos Jr, may be more pro-US than Duterte, especially given the legacy of his father. However, his decision to start the year by making an official visit to China, seeking what he called a shift to a “higher gear” in bilateral relations, is indicative of the fact that this trend of hedging between Washington and Beijing in foreign policy will continue. When visiting, it is clear he will seek to reinforce the aspect of economic ties between the two countries, but also reassure China that the Philippines will not become a mere military platform for the US.

However, how this ultimately pans out remains to be seen. It is anticipated that in 2023, the US will attempt to ramp up Taiwan tensions further. The goal of doing so will of course be to break any unity and harmonious ties between China and Asian countries, with the goal of projecting its military power further (as it has done with Ukraine). How will Manilla navigate these crises? How will it handle US requests for more and more military access? And how will China manage this situation? While the visit is promising on the diplomatic front, it tells us little about what is to come ultimately.