The region has a distinct identity and doesn’t fit neatly into either Russia or Ukraine.

Current events have brought a renewed focus on the Donbass, a historical region on the border of Ukraine and Russia. By the standards of history, this area has emerged quite recently, and has always stood a little apart. It’s important to understand its evolution when viewing this crisis, which began in 2014.

Today, Donbass is an industrial and mining region, but for a long time it was largely uninhabited. The steppe zone that ran along the southern borders of medieval ‘Rus’ (not yet divided into Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus) was called the ‘Wild Fields.’ It was home to nomadic peoples and farmers only moved south with great difficulty. After the Mongol invasion in the 13th century, the Wild Fields was a dangerous place to find yourself.

Around four hundred years, a few peasants from Russia and Ukraine began to gradually settle in the future Donbass.

A great leap forward came in the 19th century when the coal deposits discovered there became necessary for industry. It was then that many of the cities without which it is impossible to imagine today’s Donbass were founded. In 1869, the British industrialist John Hughes built a factory around which the village of Yuzovka grew – it had a few more names, including Stalino, before a local man renamed it Donetsk, in 1961.

His name was Nikita Khruschev, and he had risen from humble origins as a metal fitter to lead the Soviet Union.

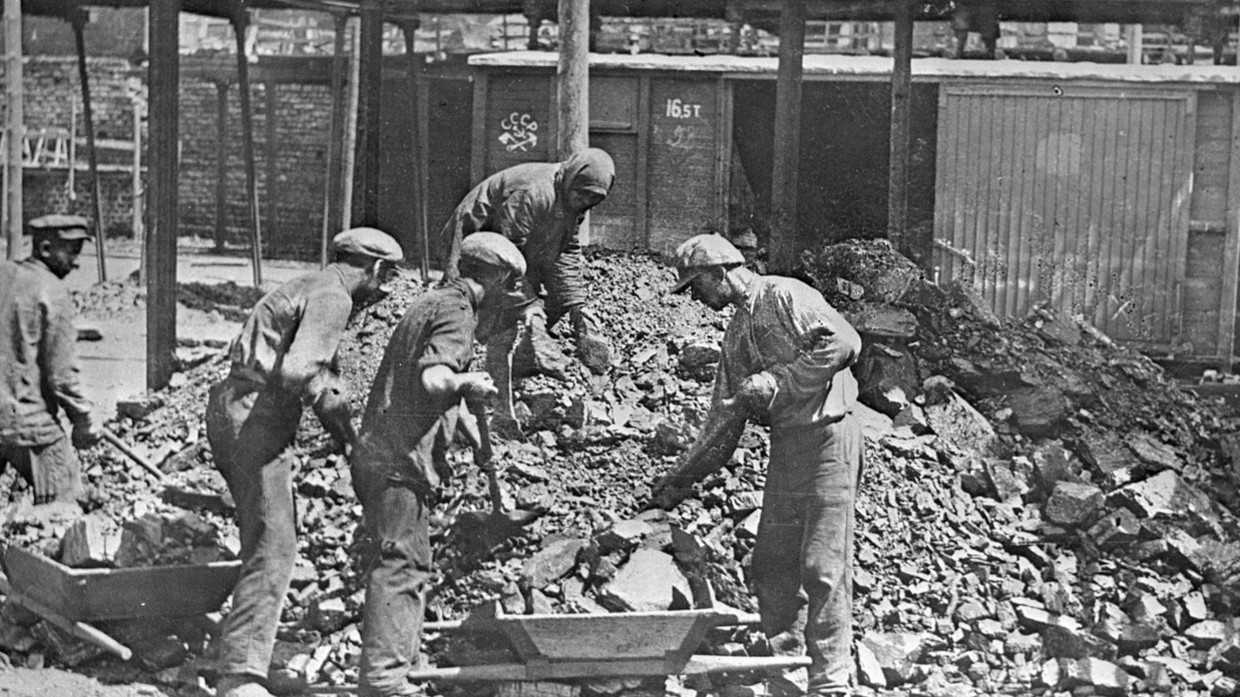

In 1868, Kramatorsk appeared and, in 1878, Debaltseve. The cities grew rapidly. Coal deposits and increasing factories formed the unique ‘face’ of the region. This even applies to the landscape: wherever you go in modern Donbass, giant landfills catch your eye. Donbass was formed as an industrial region and its cities and factories often flow into one another, even today. The region was inhabited by several streams of colonists from Russia and Ukraine and its population was very diverse, but its peoples mixed easily due to the proximity of their languages and cultures.

It was meteoric development in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when it became a huge mine and forge for the Russian Empire, that made it the Donbass we know today.

A great deal changed in 1917. Two revolutions and a civil war divided the history of the whole of Russia into ‘before’ and ‘after.’

After the February Revolution, when the monarchy fell, a Provisional Committee ruled the region. Meanwhile, the Central Rada in Kiev declared Ukraine autonomous, before making a declaration of independence after the October Revolution. The Rada made broad territorial claims, which included the territory of Donbass. However, not entirely so. Yuzovka was a border city, according to the Rada’s stipulations. The nuance was that the Rada did not exercise any authority over most of these territories, and it soon was quarreling with the Provisional Government in Petrograd.

The whole argument could have been quashed in parliamentary debates but, on November 7, 1917, the socialist revolution took place. After that, events took off at a gallop. In Kiev, the Communist uprising was suppressed, and Russian officers, who considered the Rada a lesser evil than the Reds, actively participated.

Meanwhile, in the east of the self-proclaimed Ukraine, a very unusual coalition was being formed. Its center was Kharkov, a large industrial city that was not part of the Donetsk Basin region but closely tied to it. The Donbass’ distinct identity had already emerged by that time. Although the area was administratively divided into three entities, they had a common economy and interests. While the Rada was in session, local councils in the east of Ukraine announced the unification of the Donbass and Krivbass coal basins. It also included cities belonging to the region of the Don Cossack Army, such as Mariupol and Krivoy Rog, which was administratively part of the Kherson province, as well as Kharkov. This structure, which was informally called ‘Donkrivbass’ or simply ‘Donbass,’ did not claim independence and deemed the idea of separating from Russia absurd, considering itself, instead autonomous within it. Moreover, Ukraine’s independence projects were of no interest to it creators.

Nikolai von Ditmar, chairman of the Council of Congresses of Miners of the South of Russia, noted:

“Industrially, geographically, and practically speaking, this whole area is completely different from that of Kiev. This whole district has its own completely independent fundamental importance for Russia and lives a separate life. The administrative subordination of the Kharkov district to Kiev is not called for by anything at all, but on the contrary, does not correspond with reality. Such artificial subordination will only complicate and impede the life of the district, especially since this subordination is dictated by questions of expediency and state requirements, and exclusively by the national claims of the leaders of the Ukrainian movement.”

In February of 1918, Fyodor Sergeyev, a Bolshevik known by the party pseudonym Artyom, proclaimed the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic (DKR) to be an autonomous region within the RSFSR, or Soviet Russia.

Was the DKR legitimate? No more and no less than any other self-proclaimed entity formed on the ruins of the Russian Empire, where states proclaimed their independence and then collapsed in a week. Another example was “Green Ukraine,” an attempt to found an independent Ukrainian state, near the Pacific Ocean. That project centered around the city of Khabarovsk, which today is a 8,924km drive from Kiev.

The DKR project was not the idea of the leadership of the Bolshevik Party. It appeared precisely on the basis of a regional identity that had already been formed. The leader Vladimir Lenin knew of the upcoming creation of the DKR and did not object. The borders Artyom claimed for the republic were more modest than those drawn by the Rada, but still very wide. The DKR’s problem was the same as the Rada’s – actual control over the territory was very tenuous or nonexistent. The DKR had its own government, which included representatives of three left-wing parties – the Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, and Social Revolutionaries. Some of its legislation’s nuances appear very unusual and mild by the standards of the time and place. For example, the death penalty was officially banned there. In general, Artyom and his team had a reputation among the Bolsheviks as soft-hearted liberals who hindered repression and released the ‘bourgeois’ from prison.

In short, by the standards of civil war-torn Russia, the DKR was a real stronghold of humanity. In reality, everything was not going as smoothly as the creators of the republic would have liked. For example, arbitrary reprisals were prohibited but the local authorities secretly practiced them. However, the general trend was more lenient than in other places.

The main problem was that Artyom and his comrades could not hold on to power. The German army, which was continuing its offensive during the First World War, was rolling in from the west, and Berlin’s forces destroyed the DKR by May of 1918.

Donbass and all of Russia collapsed into the abyss. At first, the Germans plundered the region. Then it became the scene of battles between the Reds and Whites – the main sides in the civil war.

However, Donbass’ ‘distinctiveness’ had not disappeared. The debate over how to deal with the area continued until 1923. The region’s place in the new order was not at all obvious. Its cities were mostly Russian in both language and self-identification. However, the occupying German forces installed a collaborationist Ukrainian government. Both Germans and Ukrainians shot political opponents and those suspected of sympathizing with the Reds. At the same time, the Ukrainian government began to implement a policy of ‘Ukrainization’ – an attempt to impose its own language and identity on the local population. One of its first orders read:

“In all state institutions of the Kharkov region, all business should be conducted only in the Ukrainian language.” Another requirement was “for all institutions to replace all writing on signs, posters, and announcements with the Ukrainian language within three days… The statements from leaders claiming that it is impossible to replace the writing in three days are not considered convincing because there are already some establishments that have fulfilled this order… If signs, posters, announcements, etc have not been replaced with those containing the state language within the stipulated period, then the designated heads of districts, transportation departments, and post offices will be severely punished according to the laws of the Ukrainian People’s Republic.”

These attempts were unsuccessful for a banal reason: there were not enough experts in Ukrainian to introduce the language in schools and offices. The situation reached the level of comedy when the head of the Ukrainization commission greeted subordinates in Ukrainian, after which everyone switched to Russian.

After the defeat of Germany in the First World War, Donbass was easily cleared of Ukrainian formations, and the real struggle began – between the Reds and the Whites. However, the issue of Donbass’ status remained in question.

Neither the Reds nor the Whites recognized any independent Ukrainian states. The Bolsheviks, however, welcomed the creation of Ukraine, but only a strictly Red one. Whatever the desires of the Rada, it could not secure its claims by force of arms, and authority on the ruins of Russia could only be imposed at gunpoint.

Artyom insisted that the region should be part of Soviet Russia, basing his argument on economic ties and the language of the population. However, this idea was torpedoed by none other than Lenin, who instantly scoffed at the idea of recreating the DKR, declaring it “playing with independence.” The logic on which the Soviet leaders based Donbass’ inclusion in Ukraine is interesting:

“Separating the Kharkov and Yekaterinoslav (today Dnepropetrovsk) provinces from Ukraine will create a petty-bourgeois peasant republic and lead to perpetual fear that the peasant majority will gain the advantage at some other Congress of Soviets, because the only purely proletarian districts are the mining areas of the Donetsk basin and Zaporozhye.”

The Bolsheviks, who were supported mainly by workers, literally hammered the region into Ukraine precisely because the industrial region was very different from the rest of the republic. Artyom died in a railway accident in 1921 and, of course, couldn’t have prevented this. Donbass was incorporated into Soviet Ukraine without any special status, and a campaign of ‘indigenization’ was launched in the region. Soviet ideology called for the culture, language, and traditions of the people who were considered indigenous to this republic to be literally implanted in the national republics. The USSR, especially in the early days, maintained a kind of governmental ‘affirmative action’ policy. One of the leaders of the nascent Soviet Union, Nikolai Bukharin, formulated the task as follows:

“One cannot even approach this from the point of view of equality of nations, and Lenin has repeatedly proved this. On the contrary, we must say that we, as a former great-power nation, must… put ourselves in an unequal position by making even greater concessions to national tendencies… Only with such a policy, when we artificially put ourselves in a lower position compared to others, only at this price can we buy ourselves the real trust of formerly oppressed nations.”

The Ukrainization of Donbass was carried out systematically, and with the rigidity typical of the USSR. All mention of times when the region was autonomous were banned, there was an attempt to introduce the Ukrainian language everywhere, and, in 1930, a number of university teachers were arrested for refusing to switch to the Ukrainian language and adopt ‘Ukrainian culture.’ The Ukrainization of the press, education, and culture continued until the second half of the the decade, when Joseph Stalin took national policy in different direction.

However, Donbass’ distinctiveness, although somewhat faded, had not completely disappeared. The region’s way of life still significantly differed from that in the rest of Ukraine. The industrial, Russian-speaking and largely ethnically Russian region retained its distinct character both during the era of incredible upheavals in the first half of the 20th century and the stagnant times of the late USSR. And it has, likewise, been preserved since the Soviet Union collapsed, in 1991.

By Evgeniy Norin, a Russian historian focused on Russia’s wars and international politics