Public health always involves tricky, ethics-based issues.

I believe that the Director General of Health Diane Sarfati has short-circuited her obligations in law, by failing to weigh up a marginal benefit of dental caries reduction, against a potential neurodevelopmental risk across all children exposed to both fluoridated drinking water and toothpaste.

She needs to be open about possible benefit versus possible risk – and the trade-off this could involve. This isn’t being done.

Evidence shows that New Zealand’s women and children have fluoride levels that are above the level where fluoride levels (in urine) have been associated with lower IQ.

The Ministry of Health and the Director General of Health Diane Sarfati have both refused to consider both the New Zealand study that shows these high fluoride levels, and the United States (US) court case that determined that the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had failed to conduct its own risk assessment.

The lawyer who represented the plaintiffs in this court case, Michael Connett, is touring New Zealand to discuss the case, starting with Whangarei this Saturday.

Connett is an expert in this matter, I’ll be interested in what he has to say about this controversy in which science, law and public health ethics overlap.

Keep in mind, New Zealand authorities have never conducted a risk assessment of fluoride.

What is Sarfati’s most important goal?

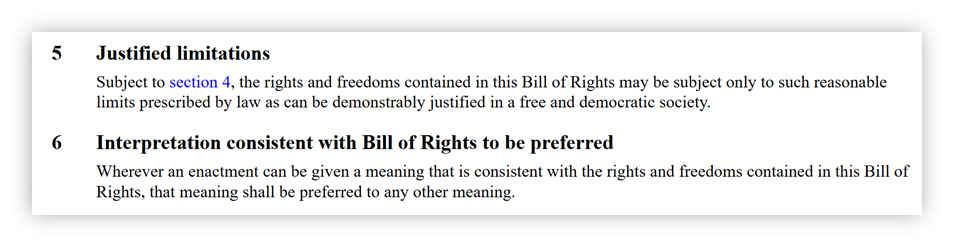

The New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 (BORA) states that the limitation of a right must be considered in light of the goal. Sarfati’s claimed goal? ‘Public health goals related to oral health’. But Sarfati is the Director General of Health (D-G). The D-G states that the:

‘oral health benefits gained from community water fluoridation are sufficiently important to justify the curtailment of the right’.

The Director General of Health believes that limiting the right to deny medical treatment is justified by the goal of a marginal reduction (reducing the prevalence and severity of dental decay [116(3)(a)]) in caries.

I believe we must question: Has the D-G ‘closed her mind’ and made a reviewable error of law? Isn’t the most important (highest-order) goal is that Sarfati must fulfill, is the protection and prevention of health (section 3A) of the Health Act 1956?

Keep in mind the BORA’s emphasis on ‘sufficiently significant’:

‘the legislative objective, in pursuit of which the measures in question are implemented, must be sufficiently significant to warrant overriding a constitutionally guaranteed right’[i]

A ‘marginal’ reduction in caries

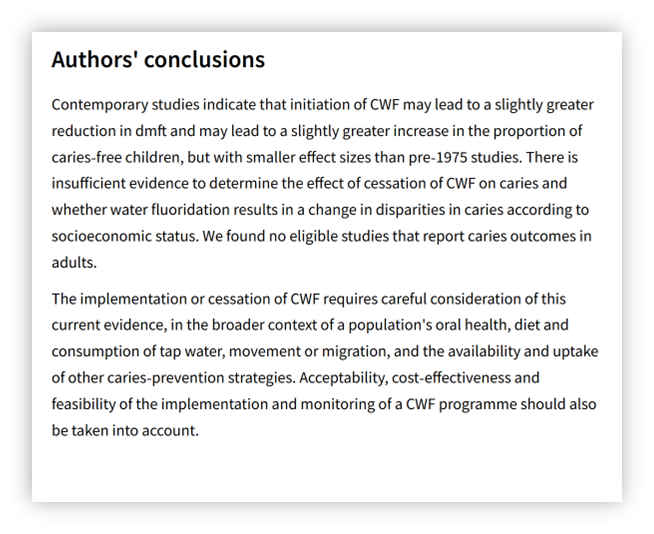

The previous D-G, Ashley Bloomfield, used the 2015 Cochrane Review to justify the mandate. However, a key finding of an updated 2024 Cochrane Review was that water fluoridation may lead to a slightly greater reduction in caries, perhaps a slightly larger increase in the proportion of caries-free children but that there was insufficient evidence to prove that such a reduction would reduce inequities based on socioeconomic status.

The MoH and D-G’s information were released two months after the 2024 updated Cochrane Review was published. If the 2015 Cochrane review was material to an earlier decision, why wasn’t the 2024 Cochrane Review just as material?

Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Walsh T, Lewis SR, Riley P, Boyers D, Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, Glenny A-M, O’Malley L. Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2024, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD010856. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010856.pub3. Accessed 15 October 2024. 157 studies reviewed.

Risk-benefit analyses are important for public-health policy as there are always ethics-based trade-offs. But the D-G has not considered the risk-benefit of a purported marginal reduction in caries with a probability of a population level risk of developmental neurotoxicity. Reduced IQ is a potential side effect of the medical treatment compound added to council water supplies: hydrofluorosilic acid (HFA).

The courts seem reluctant to acknowledge the absence of risk-benefit evaluations and that the ‘goal’, a marginal reduction (reducing the prevalence and severity of dental decay [116(3)(a)]) is a relatively minor goal (not sufficiently significant), in comparison to a limitation on rights to deny medical treatment from HFA. A rather ‘large’ elephant.

Court judgements also seem unwilling to address the broader obligation of the protection of health and the probability that lower income groups would be more greatly impacted by the loss of IQ.

‘The economic cost of a lost IQ point can be quantified through lost lifetime economic productivity [44, 45]. Overall, a cognitive skill improvement by one SD (i.e. 15 IQ points) is associated with 12% and 16% increases in annual labor earnings in high-income countries and low and middle-income countries (LMICs), respectively.’

What would a reasonable person say?

A little background

In December 2024 the Ministry of Health (MoH) released the paper: Community Water Fluoridation: An evidence review 2024. At the same time the Director General of Health Dr Diana Sarfati released her response to the Judge Radich’s November 10, 2023 finding that the Director-General of Health was required to turn his mind to whether the order to fluoridate drinking water was a reasonable limit on the right to refuse medical treatment. Sarfati’s response is published as Director-General of Health consideration of community water fluoridation under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990. However, this document does not disclose the D-G’s reasoning underpinning her opinion. It simply states that four issues are considered.

Our perspective at Physicians and Scientists for Global Responsibility.

We’ve discussed this at PSGR and we consider that firstly, the Director-General (D-G) may have incorrectly focused on an incorrect ‘goal’ – oral health. In doing so, Sarfati has failed to take into account her overriding statutory obligation under the Health Act 1956, to protect and promote health.

Secondly and relatedly, the D-G exclusively considers a single source of fluoride exposure, via community drinking water, and constrains her response to state: ‘scientific evidence shows water fluoridation at optimal levels is safe and does not give rise to significant health risks.’

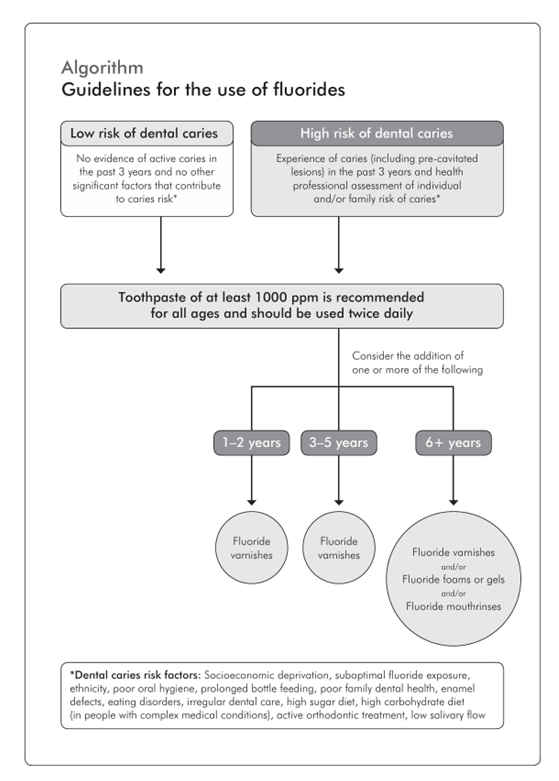

PSGR are worried that this narrowly constructed statement may mislead the public. Cumulative fluoride exposures include two government recommended activities: teeth brushing with fluoridated toothpaste and fluoridation of drinking water.

For the D-G to fully address the rights limitation and risk of harm, the D-G must recognise that ‘safety’ of fluoride exposure must take into account not only drinking water exposures but the MoH policy on fluoride.

Ministry of Health. Guidelines for the Use of Fluorides (2009). ISBN (Print): 978-0-478-33930-7.

A key finding in the US court case was that the US EPA’s failures not only included a failure to follow risk assessment guidelines, but extended to failure to establish a benchmark dose to ensure that people of all ages couldn’t be harmed from this well-established toxicant.

Benchmark dose levels must be established after identifying all routes of exposure, so as to evaluate risk from a total daily intake (as exposures).

Mischievously, the D-G of Health measures and sets how much fluoride is put into water supplies: but she does not bother to take into account the consequential quantum of fluoride and (other toxic bio-accumulative substances into the public water supplies – these include mercury, lead and arsenic) that her policy delivers into – and accumulates in – peoples’ bodies and their supportive environment over time.

The D-G has declined to address the probability of side effects from cumulative fluoride exposures. Why hasn’t the D-G considered the implications of a finding in that U.S. court case which disclosed the benchmark dose level which found that the ‘1-point drop in IQ of a child is to be expected for each 0.28 mg/L of fluoride in a pregnant mother’s urine’?

As the Judge noted, maternal urinary fluoride levels for pregnant mothers in the United States range from 0.8 mg/L (at the median) and 1.89 mg/L.

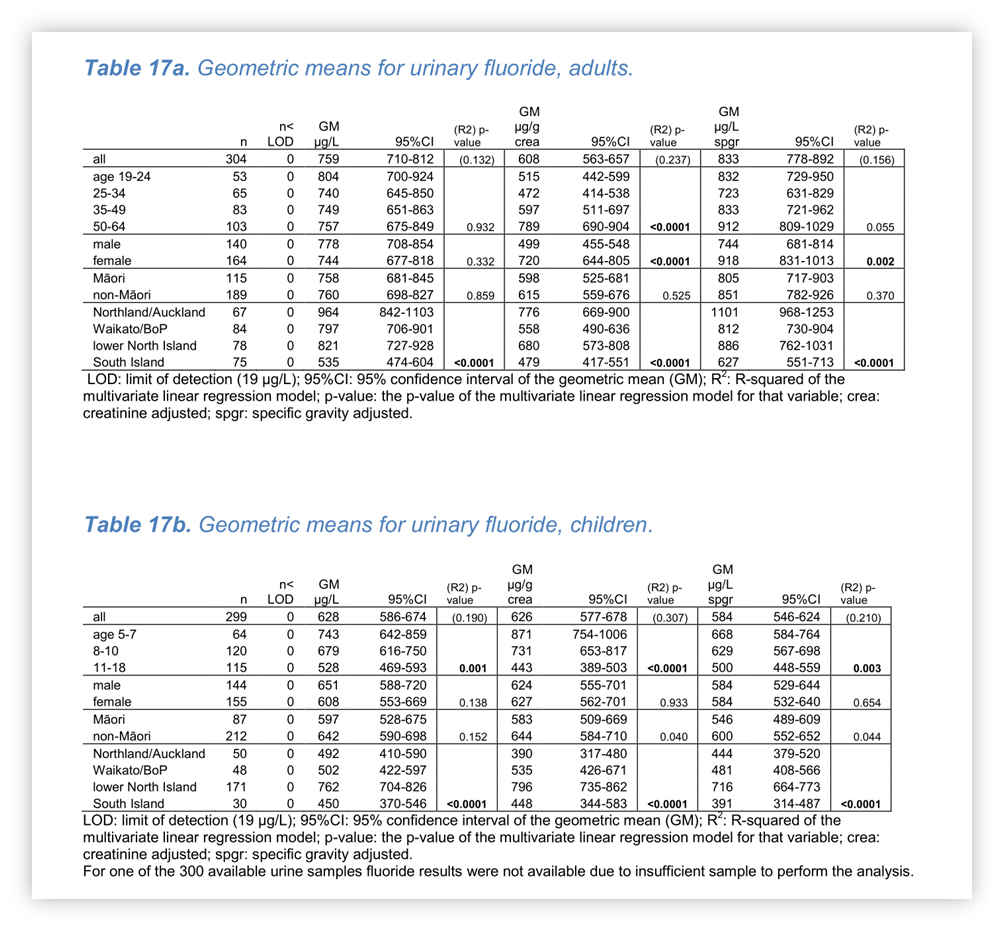

New Zealand may be similar. Andrea t’Mannetje and colleagues found that fluoride was higher in women and children:

‘Fluoride was detected in all urine samples. The geometric mean urinary fluorine was 760 µg/L for adults and 630 µg/L for children. The arithmetic mean urinary fluorine concentration was 893 µg/L for adults and 752 µg/L for children. The 95th percentile was 1760 µg/L for adults and 1600 µg/L for children. Among children, older age was associated with lower urinary fluoride levels. Among adults, a higher urinary fluoride level was observed for females compared to males after creatinine or specific gravity adjustment. This gender pattern was not observed among children.’

‘t Mannetje A, Coakley J, Douwes J. (2018) Report of the Biological Monitoring of Selected Chemicals of Concern. Results of the New Zealand biological monitoring programme, 2014-2016. Technical Report 2017-1. March. Centre for Public Health Research (CPHR). Massey University. Wellington.

Note: To convert micrograms per litre (µg/L) to milligrams per litre (mg/L) multiply the value in µg/L by 0.001 to get the equivalent value in mg/L.

The Ministry of Health and the D-G have ignored these findings.

Although the D-G claims a public health ‘mandate’, she has not demonstrated that she has considered the risks, in light of the uncertainties at play.

The D-G has failed to precautionarily consider a potential detrimental impact across the life course resulting from lower incomes, and lower quality of life, should she be incorrect. The cost of the MoH being wrong and the cost to the economy has not been factored in.

Misleadingly, all government health-based communications use the term ‘fluoride’, and the legislation states fluoride. Instead, local authorities add a compound, hydrofluorosilic acid (HFA), which contains heavy metals. This is not pharmaceutical grade fluoride. No toxicity assessments have been undertaken for HFA.

Furthermore, the D-G ignores that her toxic policy delivers increased toxins into peoples’ supportive environment via waste-water disposal systems: these toxins will progressively render water and soil-systems to become damaged and to transfer toxins to food grown ‘downstream’.

The marginal purported benefit could be ethically weighted against the potential risk from developmental neurotoxicity. While there is always a risk of confounding in epidemiological literature, there are recognised steps that decision-makers can follow to ensure maximum transparency in decision-making, and hence maximum accountability and trust in the policy process.

Administrative law principles require that the D-G should have identified, considered and given due weight to each and all of these risk considerations of actioning her fluoride policy.

The D-G has advanced no evidence (and therefore no associated and required-by-law reasoning) that she has considered these required relevant considerations.

Proportionality rule

Therefore, there is no evidence advanced by the D-G that she has ethically weighed all of the statistically-relevant benefits and risks such as to meet requirements-of-law demonstrating that her policy benefits are proportionate to the risks that the D-G’s policy generates.

A reasonable person may therefore observe that the D-G’s fluoride policy could be found – by an appropriate constitutional judicial review application to the higher courts – to be criminally negligent amounting to being egregiously negligent, or of recklessness and/or a criminal malfeasance in public office.

Sarfati, or perhaps her Ministry of Health advisers, appear ignorant of how policy is made and determined when there is uncertainty around ethics-based decisions concerning public health policy.

Navigating ethics.

Finally, with government apparently unable or unwilling to address ethics, uncertainty and policy, themes that frequently lie at the heart of public health policy, I asked ChatGPT to see if it could help. ChatGPT should not be considered the bastion of all knowledge, but the response was thought-provoking.

PSGR asked ChatGPT the following question:

If there is evidence that a mandated therapeutic treatment may cause neurodevelopmental harm in the first decade of life, but, as with most epidemiological studies, there may be risk of confounding, what would be the ethical and moral decision pathways to follow in order to confirm if the mandated therapeutic treatment should continue or be withdrawn?

Navigating such a complex and sensitive issue requires a careful and systematic approach. Here are some ethical and moral decision pathways to consider:

- Gather Comprehensive Data: Ensure that all available data, including epidemiological studies and any other relevant research, is thoroughly reviewed. This helps in understanding the extent and nature of the potential harm.

- Consult Ethics Committees: Engage with ethics committees to discuss the findings and implications. These committees can provide diverse perspectives and help in evaluating the ethical considerations involved.

- Apply Ethical Principles: Use established ethical principles such as autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice to guide decision-making. These principles help in balancing the rights and well-being of individuals with the potential risks and benefits of the treatment2.

- Informed Consent: Ensure that patients and their families are fully informed about the potential risks and benefits of the treatment. This includes providing clear and comprehensive information to facilitate informed decision-making.

- Risk-Benefit Analysis: Conduct a thorough risk-benefit analysis to weigh the potential harms against the benefits of the treatment. This analysis should consider both short-term and long-term impacts on neurodevelopmental health.

- Seek Expert Opinions: Consult with experts in neurodevelopment, epidemiology, and related fields to gain a deeper understanding of the potential risks and to explore alternative treatments or interventions.

- Transparency and Communication: Maintain open and transparent communication with all stakeholders, including patients, families, healthcare providers, and the public. This helps in building trust and ensuring that decisions are made collaboratively.

- Policy Review and Adjustment: If the evidence strongly suggests significant harm, consider revising or withdrawing the mandated therapeutic treatment. This may involve policy changes and the development of new guidelines to protect patient safety.

- Ongoing Monitoring and Research: Continue to monitor the outcomes of the treatment and conduct further research to gather more data. This helps in making informed decisions based on the latest evidence.

- Ethical Deliberation: Engage in ethical deliberation with all relevant stakeholders to explore different viewpoints and reach a consensus on the best course of action.

Here is a similar question, reframed:

How do we discuss the problem of a ‘reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified’ if one health measure (fluoridation of water and toothpaste used in teeth cleaning) might reduce dental caries by a marginal difference (but caries remain present), but the side effect of that health measure (developmental neurotoxicity) may result in lower IQ and lower income across the life course?

How do we discuss the problem of a ‘reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified’ if one health measure (fluoridation of water and toothpaste used in teeth cleaning) might reduce dental caries by a marginal difference (but caries remain present), but the side effect of that health measure (developmental neurotoxicity) may result in lower IQ and lower income across the life course?

Discussing the balance between benefits and risks in public health policy, especially when it involves potential harm, is indeed a complex issue. Here are some steps to consider:

- Evidence-Based Approach: Ensure that decisions are based on robust scientific evidence. This includes reviewing all available data on both the benefits (e.g., reduction in dental caries) and risks (e.g., developmental neurotoxicity).

- Ethical Considerations: Apply ethical principles such as beneficence (doing good), non-maleficence (avoiding harm), autonomy (respecting individual choices), and justice (fairness and equity). These principles can help guide the decision-making process.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Involve a wide range of stakeholders, including public health experts, healthcare providers, patients, and community members. This ensures that diverse perspectives are considered and that the decision reflects the values and needs of the community.

- Risk-Benefit Analysis: Conduct a thorough risk-benefit analysis to weigh the potential benefits of fluoridation against the potential risks. This analysis should consider both short-term and long-term impacts on health and well-being.

- Transparency and Communication: Maintain open and transparent communication with the public about the potential benefits and risks. This helps build trust and ensures that people are informed about the decision-making process.

- Policy Review and Adjustment: Regularly review and update policies based on new evidence and changing circumstances. This ensures that public health measures remain relevant and effective.

- Legal Framework: Ensure that any public health measures comply with legal standards and are demonstrably justified. This includes considering the legal implications of mandating certain health measures and ensuring that they are proportionate to the benefits they provide.

- Alternative Solutions: Explore alternative solutions that may achieve similar benefits with fewer risks. This could include promoting better oral hygiene practices, improving access to dental care, or using alternative methods to prevent dental caries.

By following these steps, policymakers can make informed and ethical decisions that balance the benefits and risks of public health measures.

Image credit: Getty Images

Stop eating cavity causing food would be better option.

What is so often missed is that studies proving a “risk” of something mean the adverse outcome ACTUALLY HAPPENED to some, or even all, of those studied. This s no longer just about a risk, which might not happen, of global brain damage, of which IQ tests are but one narrow measure. ALL exposed people ARE affected to some degree by chemical poisons, but especially kids. Risk is a mathematical construct, brain damage is real and disabling.

Corporate false science to justify intentional corporate state poisoning.

Is there any info about her conflicts of interest or bias that would add weight to a case?